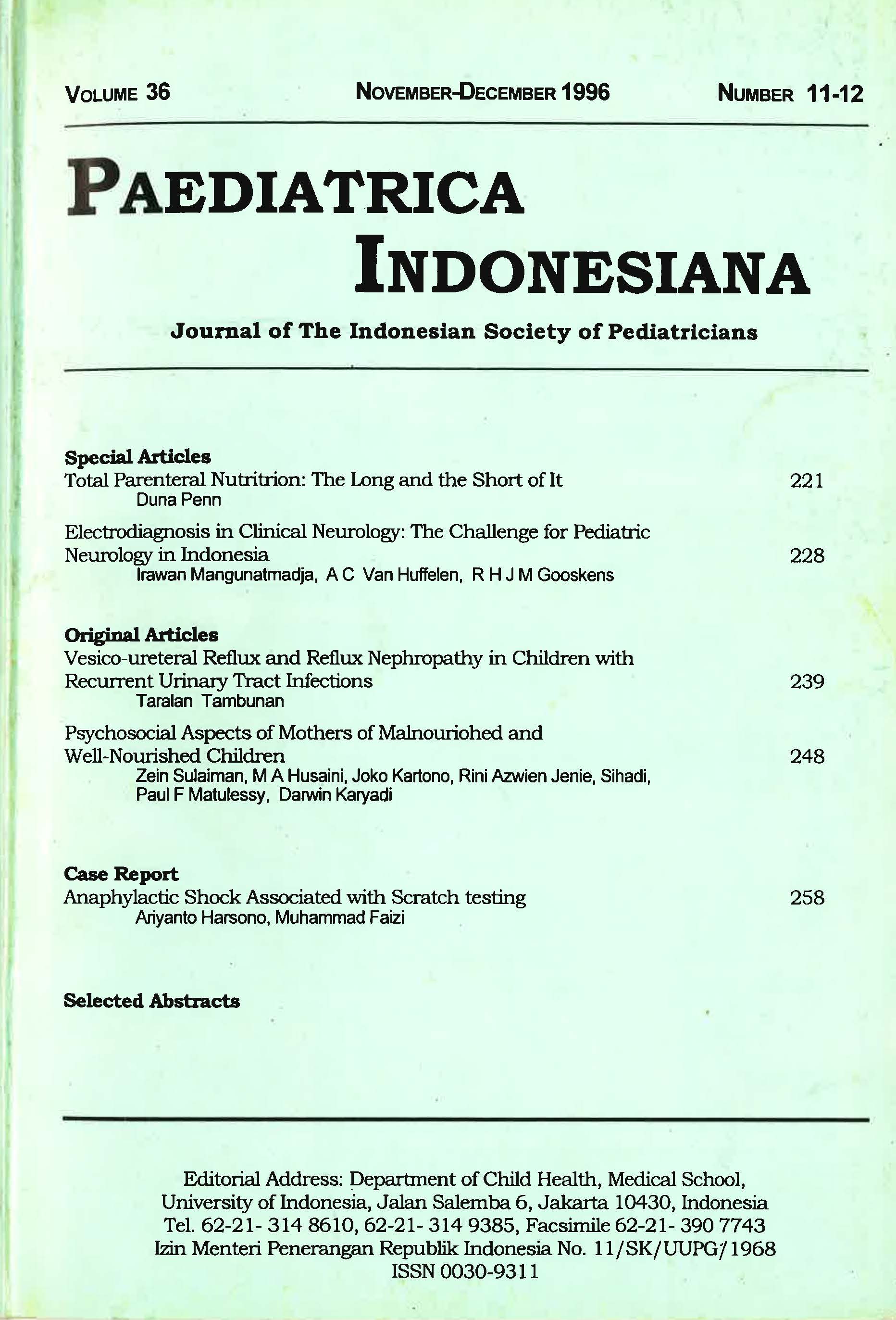

Total Parenteral Nutrition: The Long and The Short of It

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14238/pi36.11-12.1996.221-7Keywords:

parental nutritionAbstract

Within 30 years of Harvey's discovery of the circulatory system, attempts were made to utilize intravenous routes for nutrient administration.1 In 1656, Sir Christopher Wren infused wine into the veins of dogs via goose quills attached to a pig's bladder. Over the ensuing years, salt and sugar solutions, milk, olive oil, egg whites, and in later times, protein hydrolysates were tried with varying degrees of success. However, it was not until the 20th century that total parenteral nutrition (TPN) began to be viewed as a realistic therapeutic modality, stimulated by Wilmore and Dudrick's report of normal growth in a young infant with extensive intestinal atresia who was successfully mainÂtained on intravenous nutrition for over 6 weeks.2 Since then, there have been many advances and refinements, including the development of specialized crystalline amino acid solutions and lipid emulsions. Further investigation is currently underway to determine the effect of "medical foods", i.e., specialized nutrients targeted for specific purposes, e.g., glutamine for immunomodulation and intestinal mucosal preservaÂtion.3,4Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

Accepted 2017-12-11

Published 2017-12-11